"Xantha Street" is what gets me. Kees has the "angels rise" but it's "on page 289" and even though this is done "splendidly" and "to Heaven", nevertheless "the evening still comes on."

I go back to that idea again and again of the odd detail or the minor or mundane particular that in a moment takes over the whole scene. Roland Barthes described this as the punctum and Mieke Bal as the navel, among others.

"The climate of murder hastens newer weeds" and death's all around, you're "frantic, but proud of penmanship. Beasts howl outside; / Authorities, however, keep the pavements clean."

What's that slide that takes place in existence from what's taken to be important to what's not so that what's not entirely trumps the other and then becomes what is? See page 289. Feel the evening come on. Note the penmanship and pavement. Ponder the bellybutton and laugh, or get the point. Your own point as you see it, a Barthian punctum amidst the studium. -bbc

Thursday, December 19, 2013

Friday, November 22, 2013

"The Smiles of the Bathers"

"The Smiles of the Bathers"

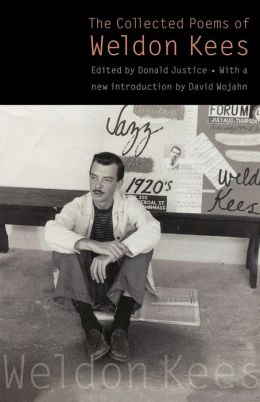

I’ve been reading Weldon Kees’ poem, “The Smiles of the

Bathers,” and thinking about the line, “Water and wind and flight, remembered

words and the act of love." It’s a list with seven stressed syllables. Out of

context, and divorced from its perfect pulse, it reads a bit too primal, as if perhaps

the poet has allowed himself to be carried too far away from the twentieth

century’s grit and tight, sidewalk pivot by bloated universals. But Kees is

better than that. The above list is neither – could never be – the poem’s

opening or closing line. Instead, it’s the poem’s central metaphor. I think we

know, or at least intuit, that any list has a tendency toward litany,

invocation and prayer when included in a poem. The string of concepts, however,

has to be considered together and, thus, constitutes a type of metaphor.

Kees

frames all of the above as “perfect and private things, walling us in” with

their “imperfect and public ending.” They are “interruptions.” And the bathers,

lovers, scholars and pilots from the first four lines, all solid, tax-paying

citizens of the above twentieth century, cannot bank on momentary smiles. They,

ironically, cannot even bank on death’s ultimate interruption, for there is “No

death for [them.] [They] are

involved.”

- G.F.A.

Wednesday, October 23, 2013

Self, Variations

Whitman’s expansive self recalls for me what people tell me about atman

and Brahman in Hinduism and confirm him as a mystic, in a certain sense.

His “mysticism” is based in “empirical” description but a phenomenon

under his description isn’t “just there.” It’s there as we’ve seen it

and experienced it and felt it. It’s there as it’s run through our

brains and been spit out as particular words. Letting words do their

work is simultaneously letting our brains do their work – that’s the

entire brain system / body, from head to toe and back again.

I need Whitman’s expansive empirical mysticism, or something like it, from time to time, perhaps often. However, there can be a disconnect, a bit of the pie in the sky, and this is where I relate sometimes more with some portions of Ashbery, where we have the expanded sense of self but now drastically more finite. I’ll never get over the first words of his I read years back, the opening of his Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (1975), opening poem,

I tried each thing, only some were immortal and free.

Elsewhere we are sitting in a place where sunlight

Filters down, a little at a time,

Waiting for someone to come. Harsh words are spoken….

(From J.A., “As One Put Drunk into the Packet-Boat”)

We might start with the air of Icarus before he gets too far, before the emergency, and before a potentially fatal fall and end up sitting right where we are, waiting, in the sun, filtering to a little spot there within eye-shot of a maple, in a squabble.

-bbc

I need Whitman’s expansive empirical mysticism, or something like it, from time to time, perhaps often. However, there can be a disconnect, a bit of the pie in the sky, and this is where I relate sometimes more with some portions of Ashbery, where we have the expanded sense of self but now drastically more finite. I’ll never get over the first words of his I read years back, the opening of his Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (1975), opening poem,

I tried each thing, only some were immortal and free.

Elsewhere we are sitting in a place where sunlight

Filters down, a little at a time,

Waiting for someone to come. Harsh words are spoken….

(From J.A., “As One Put Drunk into the Packet-Boat”)

We might start with the air of Icarus before he gets too far, before the emergency, and before a potentially fatal fall and end up sitting right where we are, waiting, in the sun, filtering to a little spot there within eye-shot of a maple, in a squabble.

-bbc

Sunday, October 6, 2013

"Love Poem Against the Spring"

I’ve been reading Marianne Boruch’s first book, View from the Gazebo, and thinking about

how sentiment may very well simultaneously be the first tool in the poet’s box

and the first hurdle a poet is obligated to overcome. It’s kind of the Chuck

Berry riff of writing poems; it cannot be denied, but must be applied with care

and timing. More specifically, I’ve been reading “Love Poem Against the

Spring,” a poem that opens with lines that neither deny nor reverse sentiment:

Spring

means nothing but camouflage

so

we dare to say these corny things.

It’s spring once more - no irony, no high-modern cruelty.

Instead, Boruch acknowledges all the existing green that any new attempt at

green blends into. She acknowledges the unavoidable matrix of sentiment that

consumes any new declaration of love, the “camouflage,” the “corny things.”

She concedes

spring and its purple flowers, but never denies her own discomfort: “OK,

they’re cute. My hunger’s not.” I like that the speaker’s ache stays complex.

She is accused of being a computer by a friend, but the calculations here are

clearly the necessary (and probably futile) steps to avoid breakdown: “Perhaps

the pretty air / exaggerates some things.” These concessions to sentiment

nearly mask the anger. The intelligence here just exasperates the sense that

the speaker, more alert and alone for defying a mindless vernal camouflage, is

utterly disconnected, and by the end of the poem she has earned her take on an

image common enough to be cliché but strangely effective in triplicate. She has

earned her collapse into a heightened state of emotion that could be

“sentiment” if decades of academic poetry workshops had not thrown sentiment

out with the bathwater:

Last

night I saw three couples, incredible throwbacks,

strolling

into the dusk, two so giddy, they’d love anything.

I’m

quiet as a brick. But for spring

this

far I’d go – glad, I guess, to shed this coat. It’s you

I

crave, you who gets more stunning

as

we age.

-- G.F.A.

Wednesday, September 25, 2013

What Works?

I keep thinking about what works. Always depends, of course, but there are some

reliables: past reading + experience along with gentle questioning of how it

feels, to begin with. Recently I keep

coming back to #132 in Complete Poems of

E.D. (T.H. Johnson / Back Bay edition):

“I bring an unaccustomed wine / To lips long parching / Next to mine, /

And summon them to drink; / Crackling with fever, they Essay….” I find this trustworthy, affectively

speaking. And by the time we get to the

last bit here my neurons are firing up, too.

So as I’m reading, I’m implicitly asking Does this feel right? but also Does this contain or expand my intellectual universe? Am I opened up and strengthened? Or am I shut down and made even less significant than I already am? When I get to Whitman’s assertions, I certainly feel the expanse: “I am of old and young, of the foolish as much as the wise, / Regardless of others, ever regardful of others, / Maternal as well as paternal, a child as well as a man…” (Leaves [1855] in Whitman: Poetry & Prose, Library of America).

I have to admit that I get a little suspicious and cautious about Whitman’s optimism and romanticism at times. Feels like we could be set up for a fall, perhaps unnecessary fall. Still, often the risk seems worth it. “A learner with the simplest, a teacher of the thoughtfulest, / A novice beginning experient of myriad of seasons, / Of every hue and trade and rank, of every caste and religion, / Not merely of the New World but of Africa Europe or Asia . . . . a wandering savage, / A farmer, mechanic, or artist . . . . a gentleman, sailor, lover or quaker, / A prisoner, fancy-man, rowdy, lawyer, physician or priest. / I resist anything better than my own diversity, / And breathe the air and leave plenty after me….”

So as I’m reading, I’m implicitly asking Does this feel right? but also Does this contain or expand my intellectual universe? Am I opened up and strengthened? Or am I shut down and made even less significant than I already am? When I get to Whitman’s assertions, I certainly feel the expanse: “I am of old and young, of the foolish as much as the wise, / Regardless of others, ever regardful of others, / Maternal as well as paternal, a child as well as a man…” (Leaves [1855] in Whitman: Poetry & Prose, Library of America).

I have to admit that I get a little suspicious and cautious about Whitman’s optimism and romanticism at times. Feels like we could be set up for a fall, perhaps unnecessary fall. Still, often the risk seems worth it. “A learner with the simplest, a teacher of the thoughtfulest, / A novice beginning experient of myriad of seasons, / Of every hue and trade and rank, of every caste and religion, / Not merely of the New World but of Africa Europe or Asia . . . . a wandering savage, / A farmer, mechanic, or artist . . . . a gentleman, sailor, lover or quaker, / A prisoner, fancy-man, rowdy, lawyer, physician or priest. / I resist anything better than my own diversity, / And breathe the air and leave plenty after me….”

-bbc

Sunday, September 15, 2013

Loneliness in Jersey City

“Loneliness in Jersey City”

I’ve been reading “Loneliness in Jersey City” by Wallace

Stevens and thinking about metaphor’s central place when committing acts of

poetry. To enter the poem we must consider its unlikely opening equation: “The

deer and the dachshund are one.” It’s odd, but far from dismissible, more than

passing strange. The stanza continues with a syllogism that never quite

resolves: “Well, the gods grow out of the weather. / The people grow out of the

weather; / The gods grow out of the people. / Encore, encore, encore les dieux

. . .” I imagine Stevens fit to be tied, at the end of his rope, so to speak,

stacking the world into probabilities as he did during his day gig as v.p. of

the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company. Nothing adds up. No foothold

presents itself. This is not whimsy, but hell for a guy who wrote in “Three

Academic Pieces,” (a Harvard lecture,) of the magic that can happen when

metaphor bridges “things of adequate dignity.” I feel Steven’s isolation

emerging as the poem goes on to surrender its street scene: its darkened

steeple and its all-night immigrant serenades.

I remember a creative writing worksheet from my high school

days. It was designed to help young people avoid clichéd expressions. Instead

of writing “busy as a bee,” it instructed, one should invent a level of

business more like, “as busy as a mustard paddle at a picnic.” I, frankly, fear

the poetry that grows out of such instruction.

-

G.F.A.

Monday, September 2, 2013

Words Work

'Words don't need to be dressed up. Words do the work themselves.' I thought this as I heard a speech recently where affect was used heavily in order to 'help' the words along. But words usually don't need help -- it just depends what the words are.

When all else fails, it's sometimes thought, insert pathos. But following Aristotle, as I was taught him, pathos emerges as a result of logos rather than added on as another strategy. (Same goes for ethos.) Why sometimes do we think words need help?

Well, sometimes they do need help, but if we're in the word business then the first attention really should go to letting words and combinations of words do their work. Perhaps from the weakness of some particular word combinations we're then tempted to play a 'pathos' card or cash in on 'ethos' as if these aren't already bound up in the 'logic' of our words.

And by logic here I don't mean syllogisms necessarily (nor even enthymemes) but whatever structure of words one strings together in such a way that works. Part of 'what works' is how these words (in any given situation) relate to other words we know. And part of what works is how these words relate to our experience -- what we feel and think.

I think of Dickinson again. She doesn't need my help in reading her -- e.g., as I read her aloud. She's done (almost) all the work, and I mostly need to get out of the way so her work can do what it does. Can we trust that the words will do their work? -bbc

When all else fails, it's sometimes thought, insert pathos. But following Aristotle, as I was taught him, pathos emerges as a result of logos rather than added on as another strategy. (Same goes for ethos.) Why sometimes do we think words need help?

Well, sometimes they do need help, but if we're in the word business then the first attention really should go to letting words and combinations of words do their work. Perhaps from the weakness of some particular word combinations we're then tempted to play a 'pathos' card or cash in on 'ethos' as if these aren't already bound up in the 'logic' of our words.

And by logic here I don't mean syllogisms necessarily (nor even enthymemes) but whatever structure of words one strings together in such a way that works. Part of 'what works' is how these words (in any given situation) relate to other words we know. And part of what works is how these words relate to our experience -- what we feel and think.

I think of Dickinson again. She doesn't need my help in reading her -- e.g., as I read her aloud. She's done (almost) all the work, and I mostly need to get out of the way so her work can do what it does. Can we trust that the words will do their work? -bbc

Wednesday, August 21, 2013

"We Humans"

“We Humans”

I’ve been reading the poem “We Humans” from Darcie

Dennigan’s book Madame X. I’m always

fascinated by how much and how little a poem can contain. Kenneth Koch once

said, “I like the idea of bringing the whole world onto the stage.” I get it.

The potential for truth and its varied rhythms becomes more likely in, not so

much an endless bucket, but a bucket in which an endless number of things might

be fetched. The sifting of more dirt unlocks more gold. The juxtaposition of

varied dirts is better than gold. The world has to be our subject and our

audience, to some extent.

The title “We Humans” stakes a claim on a pretty big

subject, but the poem’s intimacy and precision both keep its big promise in

check and ultimately fulfill it. The poem opens, “My boyfriend believes aliens

built the pyramids.” We readers get invited right into the bedroom where the

speaker and the speaker’s boyfriend watch a PBS documentary on those same

pyramids imbedded in the boyfriend’s belief. A lesser poet would mine intimacy

from the chinks in this relationship, or worse yet make a voyeur of the reader.

Sex scenes are fine, I suppose, but how many writers can truly render the act so

its mystery rivals the mystery of the pyramids?

Instead, Dennigan creates a room as fragile and uniquely detailed

as one in a handcrafted doll house: the unlit Christmas tree, those Oreos that

cross an imaginary line, the paper roses equally likely in magic and science.

The poem retains its status as miniature while still addressing belief and identity,

what we share and what we want, what we want to share but cannot. The last line

is shocking in its want. It effectively and personally calls for the world to

continue.

-- GFA

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)